The last few decades has seen an enormous increase in the range of road bike bottom bracket designs.

I take a look at the most well-known—and a few not so well-known.

I also take a look at a key development with huge implications for the road bike bottom bracket, as we know it, namely the rise (and immanent dominance) of e-road bikes which, in the mid-drive versions, eliminates the bottom bracket.

More than a minor re-imagining of this crucial bike component, the e-bike revolution may well be the end of the road…

I cover these questions and more in this reflection on the past, present, and especially the future of the road bike bottom bracket.

CONTENTS

Threaded: English, Italian, Eccentric, Other

Press Fit

Brand-Specific Road Bike BBs (Trek, Cannondale,

What Does the Surge in Mid-Drive E Road Bikes Mean for BBs?

The THREADED ROAD BIKE BOTTOM BRACKET

The design history of road bike bottom brackets is as simple as you can get. Categorically speaking, anyway.

We began with threaded BBs, ‘progressed’ to press fit, and have recently seen the beginnings of what looks like the return of the threaded BB in T47.

The first road bike model to sport a bottom bracket was John Starley’s 1885 Rover Safety Bicycle, the design that’s still with us today; the BB installed into the frame with threads.

Although there are a number of threaded standards in existence, the English standard is the most common.

English

The English threaded bottom bracket, otherwise known as the BSA bottom bracket, was — and arguably still is — the most simple and reliable road bike bottom bracket, easy to install, remove, and maintain.

‘BSA’ is the acronym for the Birmingham Small Arms Co. Established in 1861, they got into producing bike components 20 years later and enjoyed many decades in the forefront of components manufacturing (Sturmey Archer came from BSA) before eventually disappearing by the 1970s.

The spec is 24 TPI inscribed into a 34.8mm outer diameter that threads into a corresponding BB shell, with a left hand thread on the drive side (lefty-tighty, righty-loosey).

‘BSA’ BBs mostly appear in the form of cartridge BBs labelled as 1.37” x 24TPI. If you see that, you know you’ve got the right one.

Italian

Italian threaded BBs are uncommon. They’re slightly larger in diameter than English threaded (36mm vs 34.8mm), fit to a 70mm wide shell, and lack the left hand thread on the drive side—it’s a right hand thread.

Colnago and some other brands use Italian threaded on select models, with some brands even sporting French threaded models.

Eccentric Bottom Bracket (EBB)

A standard, non-eccentric BB is fixed; the bearings, and thus the crank, rotate concentrically around the spindle’s center-point—think of a top spinning in the one position.

In contrast, an EBB consists of an adjustable shell that can be rotated around the shell’s center-point, but at a fixed degree of offset—think of the moon orbiting the earth.

An EBB on an MTB is for adjusting crank height.

Rotating the EBB moves the crank spindle both horizontally and vertically; the vertical travel is also height adjustment.

Most road bike users are looking to the horizontal adjustment as a means of loosening and tightening the chain.

And those riders mainly ride fixed gear bikes.

Now, a single speed or fixie is not, categorically, a ‘road bike’ per se. But since 999/1000 fixies live on the roads around towns everywhere, we’ll include it as such … and briefly mention how an EBB is a great choice for a fixie.

But not just any EBB: First’s P237SA is unique in the way it is easily adjusted with a 3mm Allen wrench.

Other EBBs are used as the road bike bottom bracket of choice for tandem bikes, or certain classes of hire bikes.

This type of EBB fits into a non-threaded 54.5mm ID shell (68mm width…standard road bike). Turning the Allen bolts presses two brackets against the BB to hold it in place; a threaded bottom bracket then installs into it.

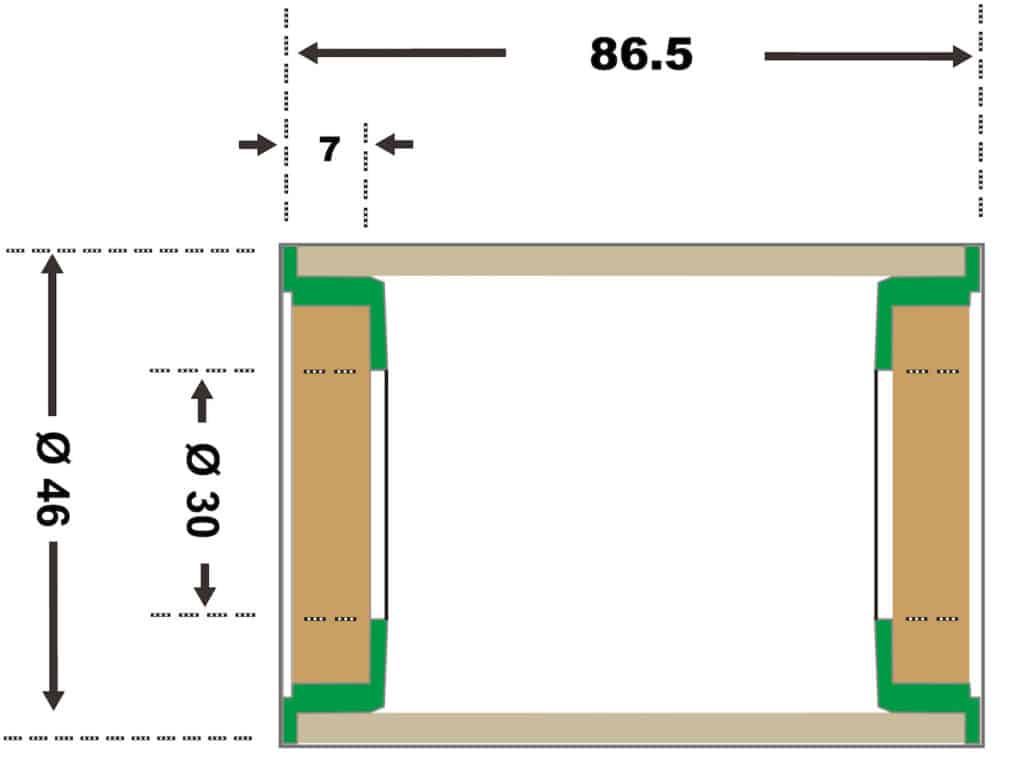

EBBs such as this model press into a 46mm shell. Tightening the bolts presses the EBB into the shell. Then you install the crank as normal.

T47

Legions of cyclists don’t have problems with press fit BBs. But for every rider that doesn’t rue the day bike companies decided that threadless (press fit) was the way to enlightenment, there seems to be one who does.

The press fit developmental saga finally ended up leaving cyclists with a generous 46mm ID BB shell (I go into the whole sordid chapter in the next section).

Cutting threads into such a shell gives you a threaded ex-PF30, otherwise known as T47.

PRESS FIT ROAD BIKE BOTTOM BRACKETS

The advent of press fit BBs was inevitable.

Bearings came to be successfully slotted directly into integrated and semi-integrated headsets, why not BB shells? An easy peasy “duh…I wish we’d thought of it” no brainer.

We’ll also have a go at answering the often unasked question — was the shift to PF the perfect example of a solution in search of a problem? — at the end of this section. (Once you abandon threads, manufacturing tolerances become hugely important.

Threaded standards worked fine as long as you used grease on the install, avoided cross-threading, and observed torque tolerances.

An even bigger question, though, is does this reflect the deeper, eternal, need for mega brands to get new kit into the market purely as a marketing tactic (think of the steady increase in cassette cogs from 10…to 11…to 12…)?

Are consumers on the sharp end of a stick thickly coated in cynicism (and some weird anaesthetic)? The muppet-engineer detesting Hambini might well agree.

BB30

Cannondale’s early 2000s monumental innovation, which landed in the market around 2006, aimed to stiffen integrated crank spindles and decrease the overall weight of a bike’s bottom bracket .

It’s a simple enough system. Instead of a redundant double movement of installing sealed bearings into the frame (BB shell) inside bearing cups, you eliminate the cups and install bearings directly into the frame.

The sequence is:

- Install C-clips

- Press-in the sealed bearings

- Install dust covers

- Install the crank

Why 30mm? Because that’s simply the next size of sealed bearing openly available.

For argument’s sake engineers could have determined that 26mm, 32mm or another size was the right way to go.

But that would mean additional expense of obtaining custom races and steel balls to produce a custom sealed bearing, which would have pushed the cost too high.

Success in manufacturing means finding a balance between innovation and production cost—you need enough margin to at least (at the very least!) cover costs whilst putting delivering the product at an acceptable price to the end user.

Anyway, the 6mm increase in spindle diameter from the standard 24mm to 30mm courtesy of a 6806 30mm sealed bearing achieves the desired effect.

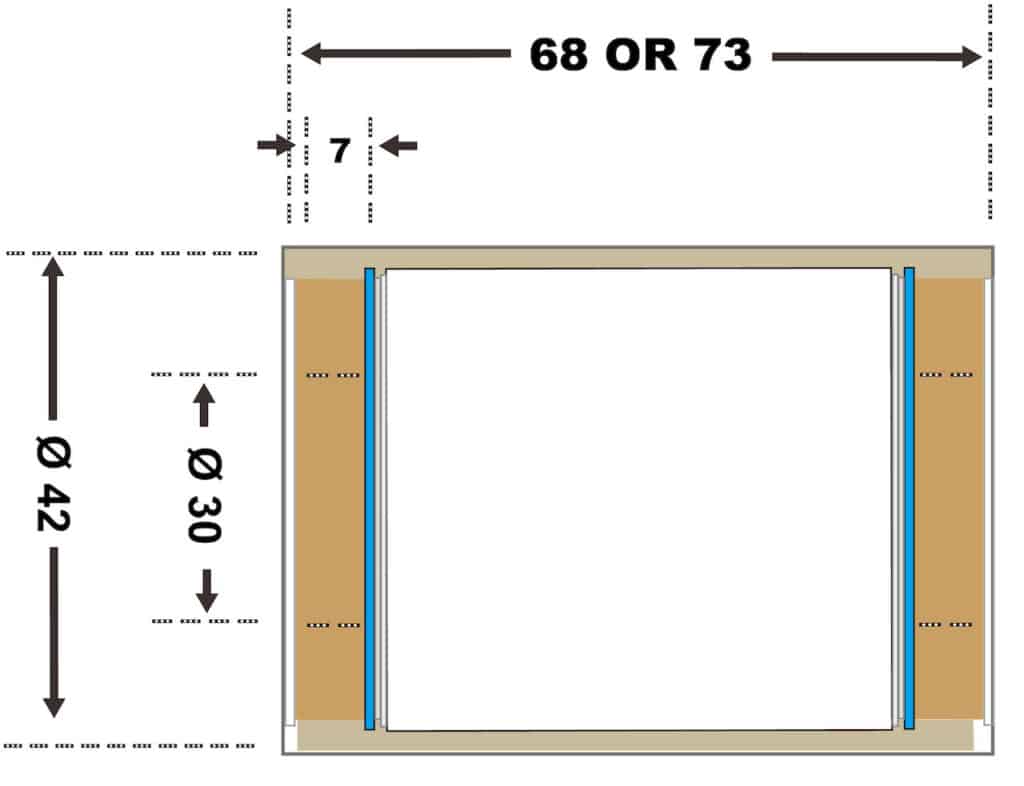

The main problem with BB30 is the fit between precisely manufactured 6806 bearings (the OD) and the particular bottom brackets shell into which the bearings directly install.

Measure a representative sample (ie. large enough) of BB shells from

- a range of brands

- various models within a brand

and you’ll find a range of variation either side of 42mm.

Sure, you’re never going to nail 42.000mm measured to the micro millimeter.

But the need for a precise fit in BB30 rigs means there’s only micro-fractional leeway, and being a few micro millimeters out can result in movement, friction and noise.

Add to this the wildcard of poor installation procedures, perhaps with the wrong tools, then the likelihood of problems is even higher.

PF30

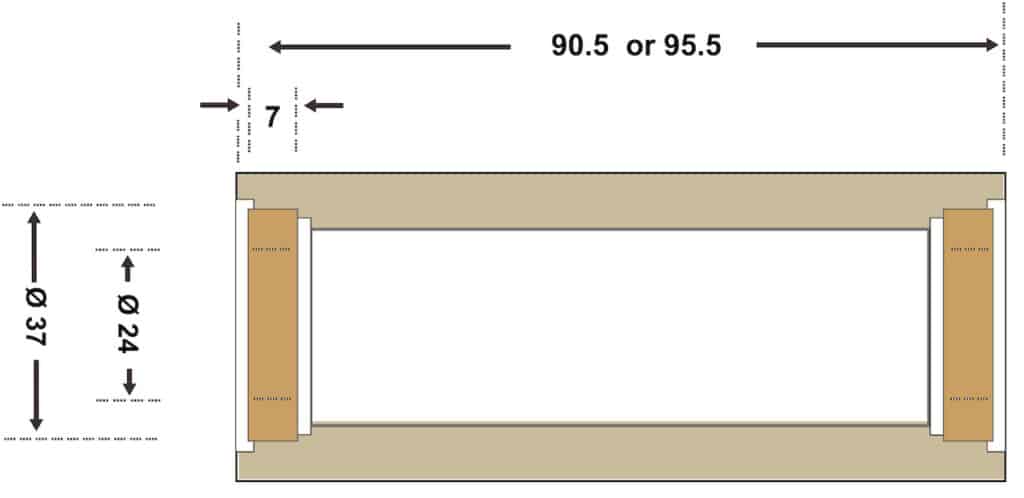

The first thing everyone wants to know is the difference between BB30 and PF30.

It’s a good place to start, since PF30 was created in response to BB30.

Come 2009, there was enough discontent towards BB30 among cyclists for SRAM to offer the solution of placing BB30’s sealed bearings back into cups which you would then press into a threadless shell.

Accommodating the 6806 sealed bearing meant increasing the internal diameter of the BB shell by 4mm, compared to BB30, to 46mm.

And that has, arguably, led to the ray of sunshine (ok…ok…depending on your perspective) known as T47 which is, basically, a threaded PF30 (46mm + 1). But, I digress.

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/rGLEN2R88lQ” title=”YouTube video player” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

PF30 requires specialist tools for installing and removing the cups without damage as illustrated in the video. To reduce the need for a range of tools or a specialist tool set such as the one demonstrated in the video, a self-installing/self-extracting model is an option.

Both the tech and the technique are simple (of course…it’s threaded!). One half of the internal sleeve threads into the other, loosened and tightened by one brand-specific (you won’t find it on Amazon) tool.

Brand-Specific PF Road Bike Bottom Brackets

An important (lamentable?) aspect of the press fit revolution is the proliferation of standards.

Once the PF genie escaped the bottle, most of the big brands came out with their own interpretation of a press fit road bike bottom bracket; and the trend has only recently reversed.

The marketing gambit is to secure or increase market share in the high-end market by coming up with a unique design that has obvious technical advantages.

Does creating a walled garden in this high-end micro-niche result an adequate financial return? Or is it better to go with an open standard and rely on different tactics to increase brand appeal?

The answers to these questions are at the heart of what has been a bewildering increase in high-tech kit, a cross-section of which I review here.

Trek BB90

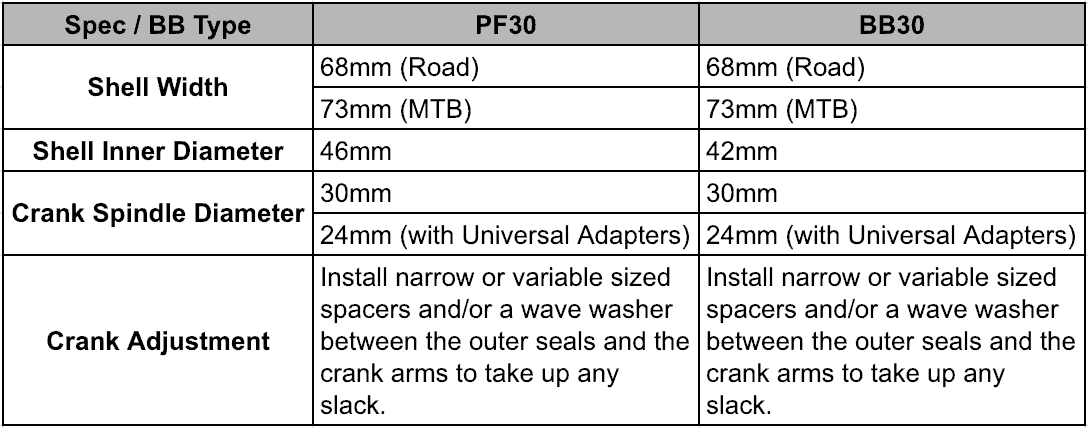

The game was afoot with Cannondale’s 2006 market release of BB30 as an open standard—the following year Trek released the BB90/95 standard countering BB30’s 30mm spindle with a conventional 24mm spindle.

’90’ referred to the 90mm width of the BB shell, not the length of the spindle; the BB shell’s ID is 37mm.

But this was not simply about tit-for-tat with a major competitor.

The adoption of carbon frames for high-end bikes was hotting up mid-2000s, and a key selling point was ‘stiffness’. The stiffer a frame, the better.

Increasing the shell width from the standard road bike spec of 68mm to 90mm adds 11mm of support around the shell on each side.

A frame maker can massively reinforce and thus stiffen the 3-way intersection of the down tube, seat tube, and chain stays to maximally resist pedaling torsional forces.

Given the non-standard dimensions, you need a proprietary road bike bottom bracket to fit—enter BB90 (95 for MTB).

Trek has abandoned BB90 on Domane, now going with a threaded T47 BB which eliminates press fit woes by returning to a standard as T47 is adopted by more brands as we head deeper into the 2020s.

Cannondale: BB30A & BB30-83 Ai

Along with introducing press fit into cycling tech with BB30 as an open standard, Cannondale have also designed their own proprietary variations: BB30A & BB30-83 Ai

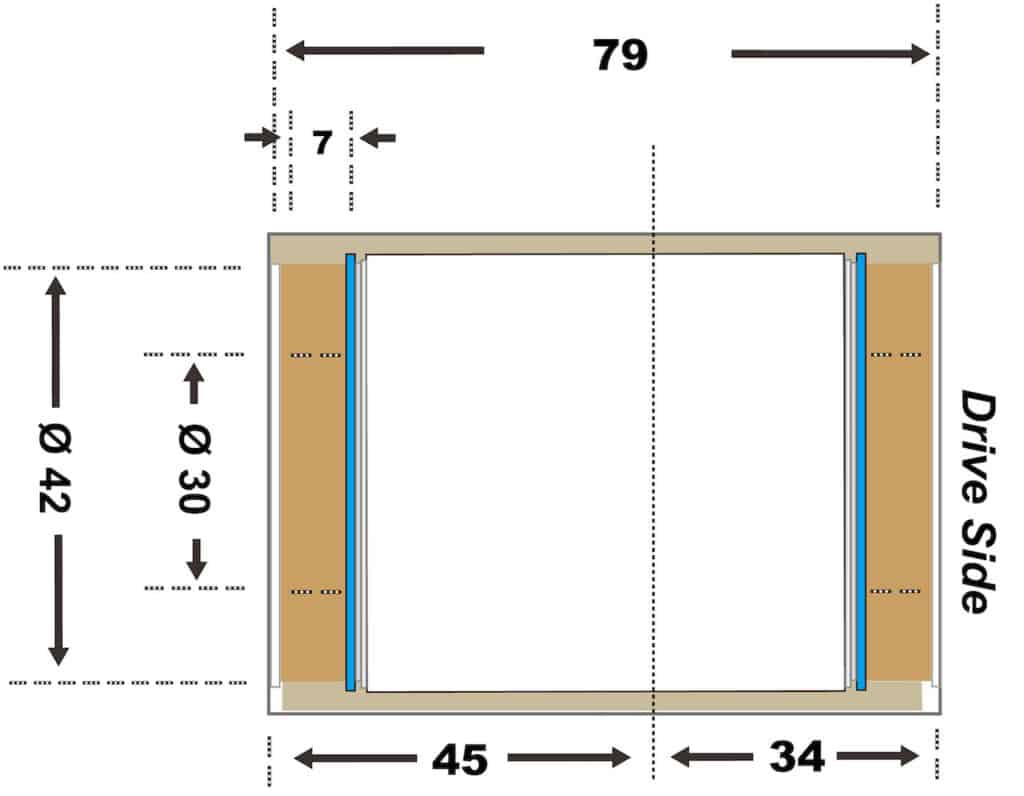

‘A’ means asymmetric. The BB shell housing this assembly is 5mm wider than BB30 on the drive side which allows for wider spaced bearings the objective being enhanced spindle support. BB30-83 A requires a BB shell width of 83mm.

And brands issuing new PF designs have made asymmetry central to their quest for a unique selling point.

Cervelo – BBright

In 2010, the year after SRAM introduced PF30, Cervelo introduced their version.

The USP is the asymmetry between the drive and non-drive side.

Cervelo added 11mm added to the non-drive side. This allows a larger, stiffer down tube and seat tube (cf. Trek BB90) and wider of the rear triangle which also increases frame stiffness. The asymmetry ensures fixed clearance between crank, chain rings, and chain stay.

FSA BB386/392 Evo

Five years into the press fit experiment that was polarizing cyclists into those that loved PF and those that hated it, FSA called ‘time’ and initiated the first effort to re-unify standards in 2011 (SRAM’s DUB being one of the most recent examples).

A variation on PF30, the idea is to accommodate both BB30 and BB86 (using adapters)

Colnago ThreadFit

Colnago’s C60 ThreadFit 82.5 is a sleeve that can take any BB86 (86.5mm to be exact).

The updated C64 82.8 got rid of the sleeve, opting for bonding a threaded alloy insert into the (carbon) frame. Which makes it a threaded system tapping into the still emerging zeitgeist that produced T47: threaded is probably best!

Specialized OSBB

Specialized’s Oversized Bottom Bracket is a variation on PF30: it sports a 68mm wide shell with a 46mm ID.

Final Thoughts on Press Fit

PF is a good solution for the majority of cyclists who use it.

Many experience no problems at all; many, however, put up with constant problems, with a significant group convinced that abandoning threads was a very bad idea.

PF systems promised weight savings and greater efficiency, which they delivered at a meaningful level for the top-tier of pro-peloton cyclists.

If you’re an average cyclist, of course, dropping a kilogram or two—and most of us have many kgs to spare than one or two—has the same effect.

Even the weight loss from dehydration during a ride greatly exceeds the weight efficiency (where weight is really saved or course…) of PF over threaded.

So were the marginal gains worth the cost? Probably not. But, then, for the true fan of cutting edge bike kit, it really doesn’t matter.

As I write, there are some signs of a move back to threaded road bike bottom brackets.

I say “some” signs, since the big brands continue to produce updated models fitted with their proprietary press fit BB systems.

The question that seems to be growing in relevance daily, however, is could it be possible that the mass move to mid-drive e-bikes will eliminate bottom brackets completely (discounting from hub drives)?

THE E ROAD BIKE BOTTOM BRACKET REVOLUTION

The summer of 2016 witnessed the transformation of e-bikes (when top-tier European mountain bikers began riding eMTBs and gave them the stamp of approval) from a small, specialized class of bikes into the key driver of the bike industry from 2020.

Although the Covid-19 pandemic helped with momentum, the die were cast several years prior to the e-bike demand-generating disruptions of 2020-2021.

We will likely look back upon 2020 as maybe not heralding the end of the road bike bottom bracket, but certainly the beginning of the marginalization of what has been a core component of bikes since the Safety Rover revolutionized cycling in the mid 1880s.

Conventional bottom brackets (probably mostly cartridge square taper) will live on for the small group of consumers using conversion kits as a cheap means of creating an e-bike from an old steed.

Otherwise, the increasing number of brands offering mid-drives with integrated and automated shifting will dominate with ne’er a mention of a “bottom bracket”.

CONCLUSION

The road bike bottom bracket was unchanged for decades up until the adoption of sealed bearings.

The introduction of press fit resulted in brands producing a wide range of proprietary designs and open standards which remain in the market, in one form or another.

As the new category of mid-drive e road bikes continues to rapidly expand, many erstwhile road cyclists will make the switch, thus reducing the demand for conventional bottom brackets.

The road bike bottom bracket will be around forever. But the days of runaway innovation are gone and we’ll likely see a reversion to basic designs as dwindling demand makes keeping the more funky PF BBs in stock unviable.