A bike’s chain line is a simple yet misunderstood but also absolutely crucial element in modern bike design, especially for manufacturers.

Why is the chain line important and who exactly should worry about it? (Hint: it’s a crucially important and potentially a deal-breaker for manufacturers and brands. Keep reading for the details).

CONTENTS

What is the Chain Line and Why is It Important?

Chain Line and MTB Geometry

49.25 | 50.25 | 52.25 | and 55.25 Chain Line Cranks

What is the Chain Line and Why is it Important?

The chain line involves two elements:

- the distance between the geometric center of the bike frame center to the chain ring, or the ‘ideal’ chain line.

- the relationship of the ideal chain line to the angle of the chain on a bike and thus the chain’s efficiency.

And #2 implies takes you into the real-world effects of different chain lines: the chain line of a double chain ring crank chain rings falls between the rings; a triple chain ring’s chain line aligns with the middle ring.

And when you add the variable of a multi-cog cassette, the drivetrain in action is only briefly in a state of a perfect chain line.

Working the front and rear derailleurs continually moves the chain through the ideal chain line from one side to the other.

The crossover angles are often extreme and the advice is always, of course, to avoid cross chaining due to the extra wear and tear on the chain, chain rings, and cassette cogs—extreme angles are also super inefficient.

As an aside, equivalent gear ratios equivalent to extreme crossover angles are easily achieved on bikes running a double or a triple chain ring.

1x systems are now standard for serious mountain bikers so we’ll focus on 1x setups exclusively here and showcase FIRST’s range of products that make it possible for a brand to design a range of models with several chain lines.

The Ideal Chain Line

Every bike has an ideal chain line.

Measure the number of millimeters between the center of the frame and the chain ring—the measurement should be calculated at an angle of 90 degrees square to the frame’s center line.

This measurement is the chain line.

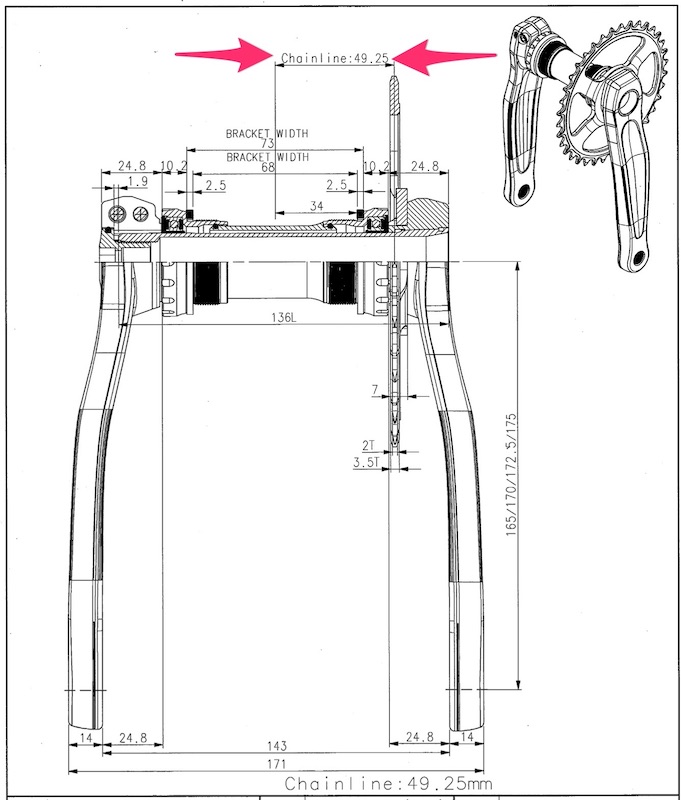

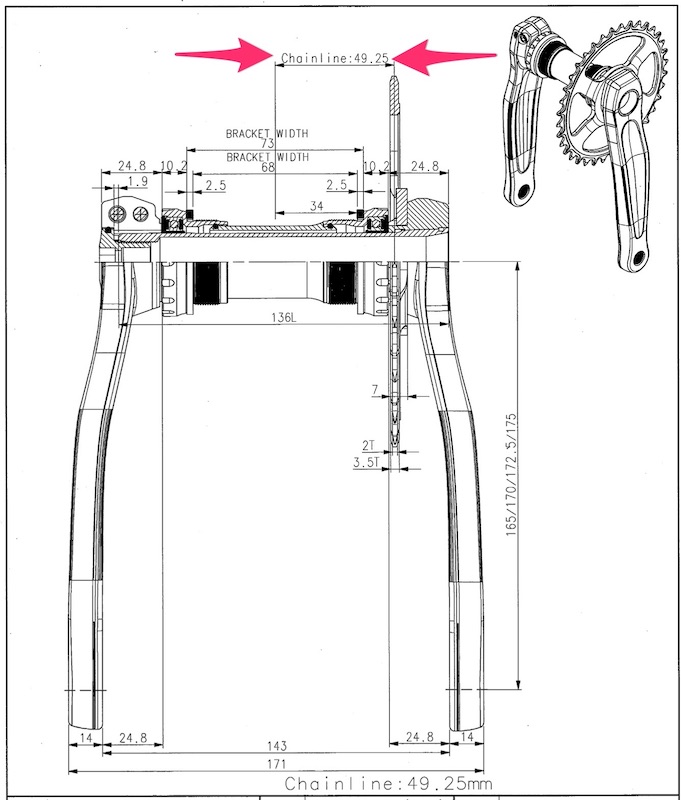

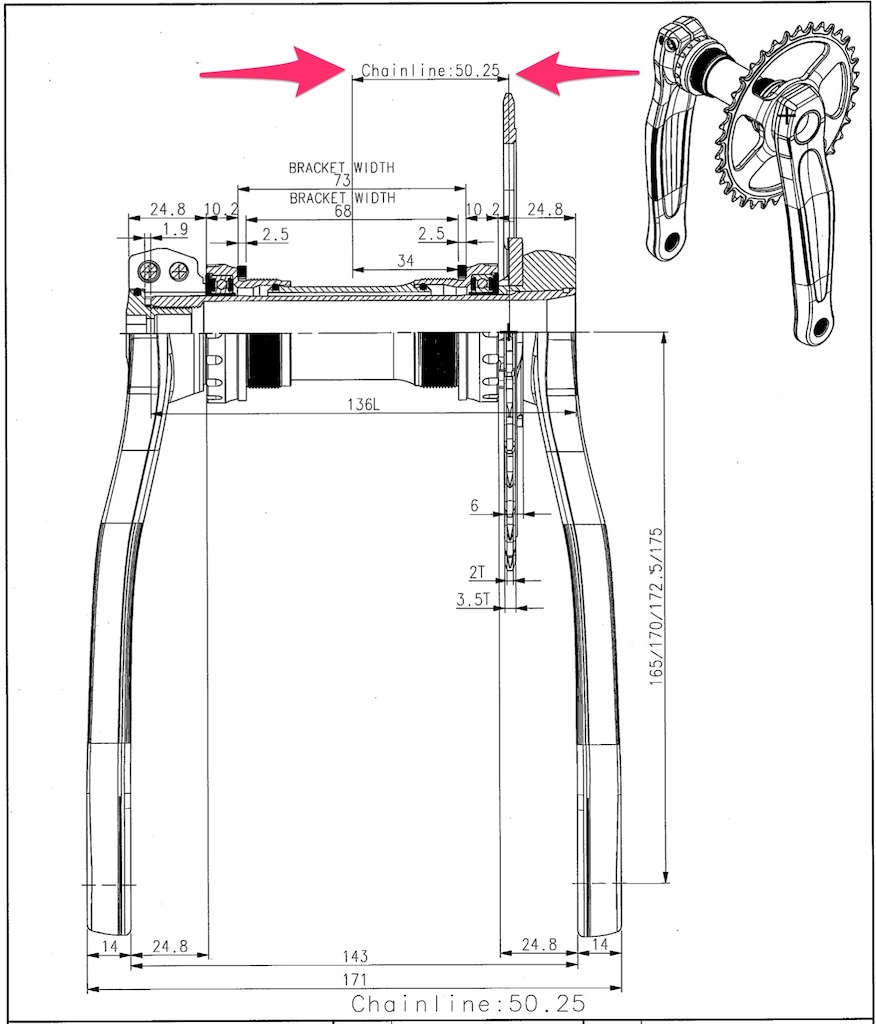

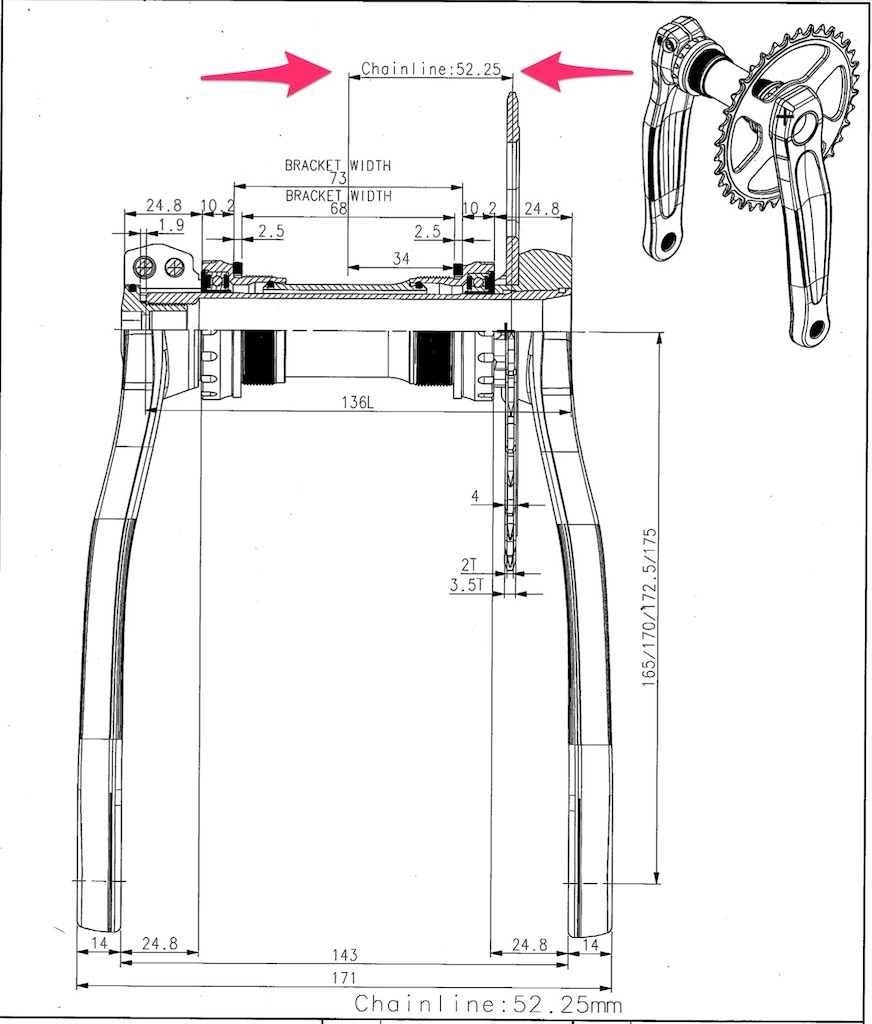

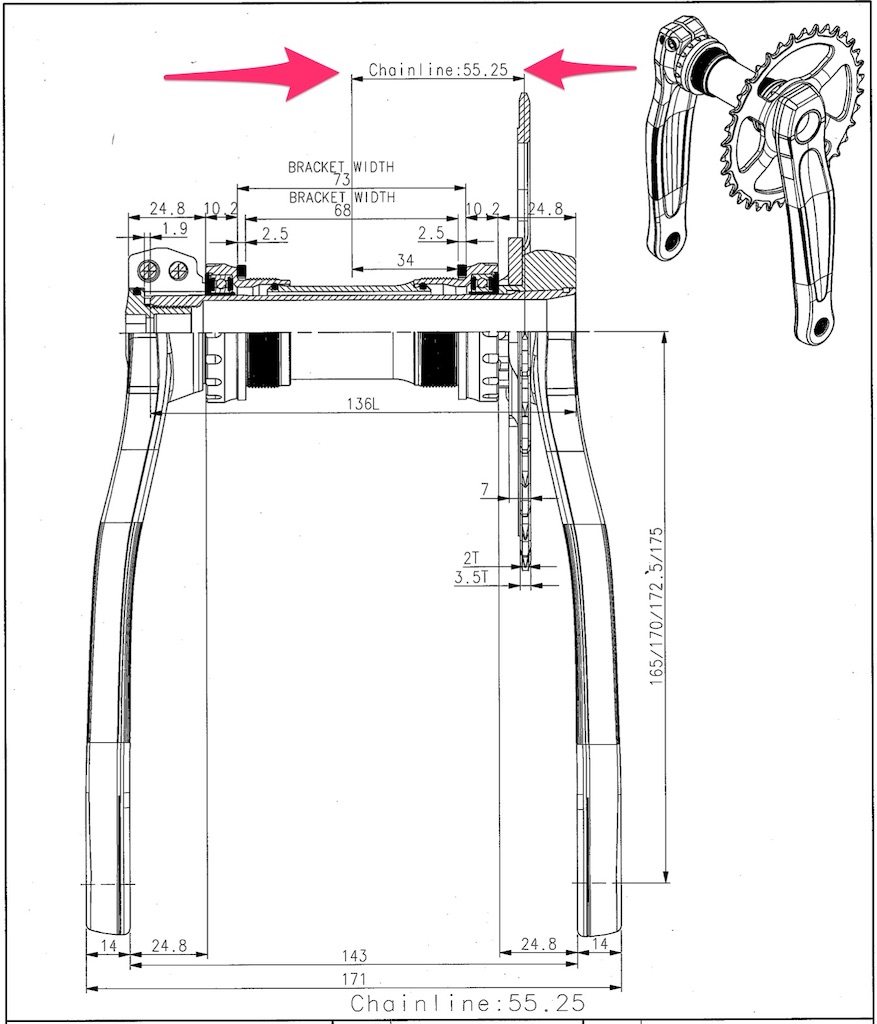

This is the engineering drawing for one of FIRST’s four direct mount cranks each offering a different chain line.

The middle of the bottom bracket corresponds to the exact center of the bottom bracket shell which is also the frame’s geometric center.

A chain running in a straight line to a sprocket that is the same distance away from the center line of the frame would give you a perfect chain line; “perfect” in its alignment between chainring/crank and sprocket.

With a 1x setup and a single sprocket—as with a fixie or bmx—the rider will always be riding with a perfect chain line.

That’s fine. But gears dominate mountain bikes and expanding numbers of cogs together in the circumference have super-sized cassettes: an 11 speed cassette could range from 10T to 42T or 46T; a 12 speed cassette could range from 10T to 51T.

Determining the ideal chain line in bike design is crucial and is factored into every model.

The chain line then determines what crank and cassette combinations are possible for a given design.

As Shimano is the market leader in drive train components brands as a rule follow Shimano specifications, all of which are predicated on chain line values for each component.

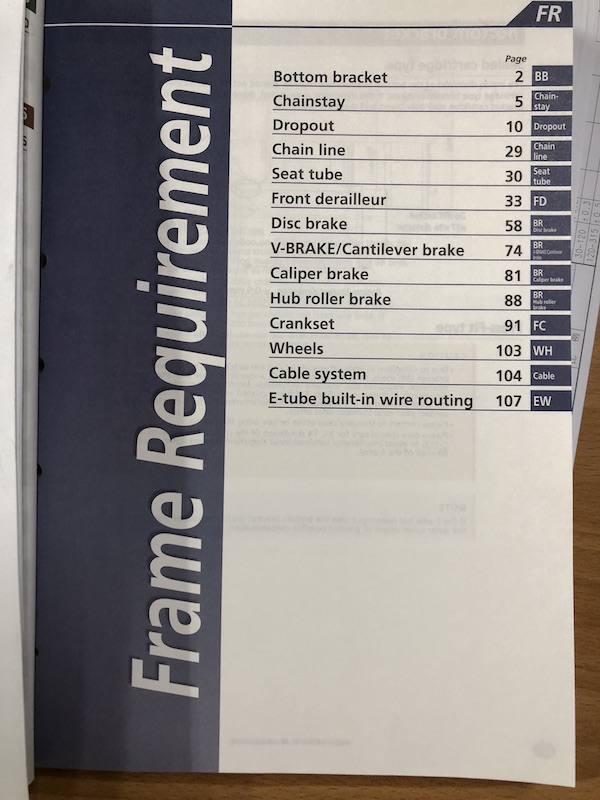

This confidential manual, issued anew for every product year, is the bible for brands and manufacturers throughout Taiwan and elsewhere.

Whatever you have in mind, if you intend using Shimano or Shimano-compatible components, these are the specifications you’d be working from when discussing frame geometry with your manufacturing partner.

Shimano’s dominance does not mean brands cannot depart from Shimano orthodoxy though. They can and do (quite apart from SRAM)—it’s a considerably sized niche market we at FIRST service with our range of products, including a selection of direct mount chain ring cranks ranging from a 49.25mm chain line at one end up to 55.25mm at the upper end. More on this below.

Chain Line and MTB Geometry

Because 1x systems are now standard for serious mountain bikers, the cutting edge of MTB design is moving in the direction of increased drive chain clearance at the crank and the sprockets.

The clearance is needed for wheels which have become larger (and stiffer) which is in turn made possible by wider hubs.

A wider hub pushes the cassette further away from the chain stay which has in turn mandates an increased chain line at the crank.

A rough guide to the developments over the last decade or so is something like this . . .

We began with the standard quick release skewer through 130mm, which increased to 135mm with a chain ring in the order of 47.5mm in on a triple or double chain ring crank.

The arrival of (non-Boost) thru-axles of 142mm accompanied a chain line increase to 48.8mm which is rounded to 49mm for discussion sake.

Then Boost hubs allowed hub flanges to be set even wider apart which allows the construction of laterally stiffer wheels; the axle increased to148mm, the chain line to 52mm with a 55mm chain line also an option.

The next step, the Super Boost thru-axle, mandates a chain line of 56mm. (The merits of yet another increase are detailed in this Singletracks article.)

49.25 50.25 52.25 and 55.25 Chain Line Cranks

FIRST Components caters to smaller, independent brands in addition to OEM and ODM production for the bigger brands and we offer a selection of direct mount cranks designed around those chain lines.

Why approximately?

Well, when you’ve got a front derailleur and shifting between two chain rings or amongst three chain rings, there is no room for error—tolerances must be precise. Otherwise shifting gears would be awful with frequent chain drops.

But with a 1x crank and no shifting, chain line tolerances are acceptable to 1mm.

So 49.25mm could comfortably be 49.45mm or 48.89mm—as long as the chain line is within 0.5mm either side of 49.25mm, the chain will run onto the chain ring smoothly whether on the highest or lowest cog (although not as smooth as in the middle when the chain is closest to the [ideal] chain line).

Despite Shimano’s orthodoxy and SRAM’s solid following, one important reason brands choose alternative chain lines is due to widely varying tolerances from some frame makers.

Take for example a brand taking delivery of a production of frames from a factory after the crankset had already been designed and produced. It then turns out the tolerances are outside what they should be, resulting in a chain line across the production not optimal for that crank.

To avoid this, the crank can be optimized to the optimal chain line of the frame once the productions’ tolerances have been determined.

FINAL COMMENTS

Casual riders won’t ever have to think about their bike’s chain line.

For dedicated or pro MTB riders, their chain line is a key variable affecting the quality of the ride.

The chain line variable is a key issue for brands and manufacturers who have to ensure the crank falls within the prescribes tolerances of the chain line of a particular production.

With that in mind we have made available a range of direct mount cranks covering the chain lines most commonly used in modern MTB frame geometry.

They are the “raw material” for ensuing that the crank can always be made to match a particular production of frames in an age where manufacturing tolerances can vary widely.